What is Attention Diversion Training (ADT)?

We have all heard of athletes who sustained injuries and didn’t even notice until later because of the melee of the game. Their attention was focused elsewhere rather than processing pain. In ADT, we leverage this principle to detach from whatever is hijacking your attention.

What are the benefits of ADT?

Attentional networks in our brain are important in processing all of our experiences. By strengthening our ability to leverage these networks to our advantage, we can improve many different experiences including pain, stress/relaxation and cognitive abilities.

What are the neuropsychological principals behind ADT?

We need to know a few principles about attention:

- You can maintain your attention on only one thing at a time.

- Only you can decide on what you choose to focus.

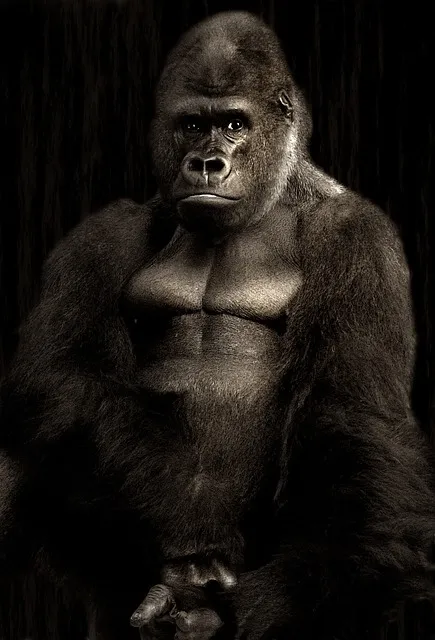

- It is very challenging if not impossible to stop paying attention to something (as stated in the Ironic Processing Theory) unless you focus on something else. For example, if I ask you to not think about orange gorillas, it’s very hard to achieve and takes a lot of energy to do unless of course you think of blue unicorns instead.

An analogy that Dr. Paul Martin uses to describe this technique is one of a flashlight:

- Only objects in the projected light can be seen clearly.

- You can move the direction of the flashlight from place to place.

So, the goal of ADT is to direct this flashlight (i.e., of attention) away from the hijacker (to something else) so that the suffering associated with hijacker falls by the wayside. As such, success with this approach revolves around strengthening skills of attention/concentration; this can be practiced.

How do I get started with ADT?

The first step to take is to become aware of how your attention works. What does it feel like to direct it to something? What does it feel like to avoid thinking about something? What does it feel like to redirect your attention to something else?

Directing your attention

We will experiment with focusing one’s attention on the picture below (or you can do this with any object or even a sensation) and letting everything else other than that object fade away.

Direct your attention to the image below. Focus on it with all of your attention. Were there any distractions? Where did focusing on this picture take your attention?

Restraining your thought

We will experiment with what it feels like to not think about something.

Look at the gorilla image above. Now for the next minute avoid thinking about that. Were there any distractions? Where did not focusing on this picture take your attention? How much energy did it take to do this?

Redirecting your attention

We will now experiment on what it feels like to drop attending to one thing, and paying attention to another thing.

Focus on the gorilla image above. Now, move your attention to the piglet image below.

Were there any distractions? Where did focusing on this picture take your attention?

Maintaining your attention on something in the face of distractions

We will now experiment on what it feels like to try to maintain attention on something while you are faced with other things also competing for your attention.

Focus on the rooster’s crest in the video (link below). If you like, you can pretend that this rooster’s crest represents your problems. It can represent your headache, or racing thoughts you experience when you’re trying to fall asleep. Note, the video below takes about 5 minutes but you can just do a minute to get an idea of the experience we’re trying to highlight. Afterwards, reflect on how much energy this took and where your attention wanted to go, naturally.

All of these exercises were meant to get you more familiar with how your attention works. Fostering this awareness is an ideal place from which to start attention training.

How do I train attention diversion?

We will borrow some terminology from mindfulness practice in discussing how to get started. The first phase of training focuses on developing control of attention. Ideally, one will practice when feeling well and free of distractions so that training is effective. The protocol published by Dr. Paul Martin is broken into two phases.

Phase 1

1. Open-monitoring: Just sit calmly and pay attention to what has your attention. Just observe these thoughts come and go. It is like taking your kid to the park. Rather than run after the kid hither and tither, you just sit patiently and when the kid tires, they will come back to you.

2. Closed-focus: Here you will now direct your attention on a specific thing. These things can be categorized as internal and external.

-Internal stimuli: This refers to focusing on something in your body like your breath.

-External stimuli: This refers to focusing on something external to your body like noises in your surroundings.

3. Redirecting your focus: Then you will explore changing your focus from one-thing to another, and paying attention to how clear the object of your attention is, and how other objects/thoughts fade from your awareness.

4. Forcing yourself to stop focusing on something: This involves experiences the amount of effort is required to not think about something (e.g., orange gorillas). Then compare this to how much easier it is to accomplish this (e.g., not thinking of orange gorillas) by thinking of something else, (e.g., blue unicorns).

5. Rate the attentional control you think you achieved during this session.

This protocol is followed daily for 10-minutes per day.

Phase 2

The second phase of training focuses on using attention-diversion strategies to control the undesirable experience (i.e., hijacker). There are four categories of attention-diversion that will be trained:

1. Internal

-Mental activity: e.g., mental arithmetic, reciting prayers, remember lyrics from popular songs, making lists of tasks to be done over the weekend, etc.

-Body processes: directing your attention to other parts of your body that are not bothering you, like your breath, or parts of your body that are relaxed and comfortable.

2. External

-Focusing on features of your environment: counting tiles on the floor, studying the construction of objects in the room; observing the varying landscaping designs on your street; or the different models of homes on your street; detecting the different sounds in your environment; etc.

-Becoming involved in tasks that distract from the uncomfortable experience: this can be a task that is demanding enough that it will engage your attention (withdrawing your attention from the hijacker) but not too demanding making it too difficult to do while being distracted by the hijacker. With practice, you may find that you are able to handle more and more demanding tasks using this strategy.

Obviously, the more interesting you make the object of your attention, the more successful you will feel. This protocol is followed daily for 10-minutes per day.

How do I strengthen skills of attention?

Practicing the protocol above daily will help strengthen your brain’s attentional control. Practicing when you are feeling well and energetic is ideal. Starting with easier challenges and working up to more difficult challenges (in contexts with more distractions) will further strengthen your attentional control.

Reference

Martin, P. (1993). Psychological Management of Chronic Headaches: Treatment Manual for Practitioners. Guilford Press.